Preparing

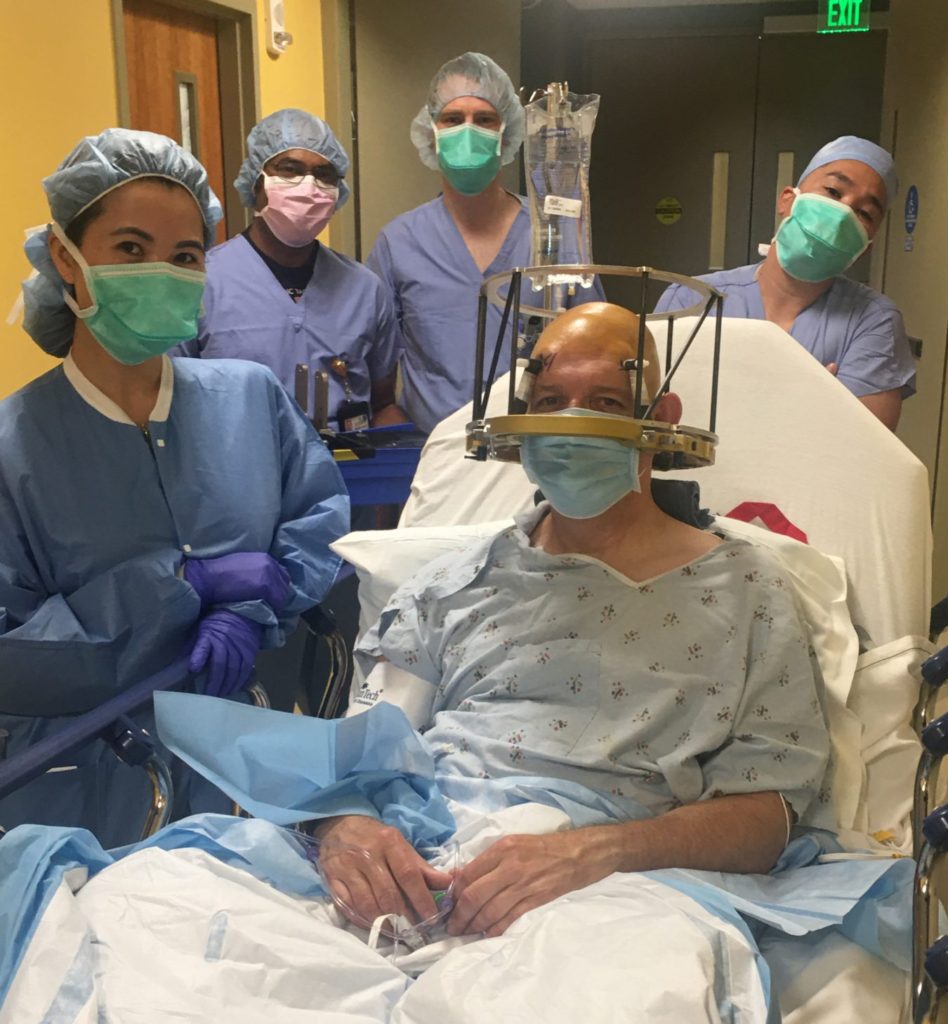

On July 22, 2021, after so much planning and thinking and worrying and anticipating and celebrating and researching and introspection, the day of my scheduled DBS surgery finally arrived. There was no turning back and I was fully prepared to embrace this next adventure in my life.

I arrived at the hospital at 6:00 am and, after checking in and verifying all of my information including a hard copy of my durable medical power of attorney, I was escorted into a pre-op area where I was instructed to change into the notorious open-back gown and do one additional body scrub with antibacterial wipes. I had also done an intense shower/pre-scrub ritual the night before. Peter was with me during this whole period and helped me navigate everything. Since my last dose of Rytary was at 11 pm the night before and I had not taken any that morning, I was feeling quite dystonic, my right leg and foot were spasming intensely. Of course, the stress of the situation only made the symptoms worse.

Clipping

A few minutes later Ivan, who would be the onsite PA for the surgery, came and clipped off all my hair. Peter snapped a picture for me and, to be honest, I was quite relieved that my bald head was not as unsightly as I had imagined it would be. Again, I’ve learned to take solace in the small victories.

There were five patients in the pre-op area and at precisely 7:45 am they rolled us all down together, one after another, to the operating rooms. It felt highly organized; almost as if we were a new Olympic event – synchronized surgery.

Rolling

As we rounded a corner and came to a bank of elevators, it was time for me to tell Peter goodbye. At that moment, I found myself fighting back tears. It wasn’t out of fear for what was about to happen, but a realization of how much I deeply loved this man who came into my life almost 25 years earlier and, despite never intending to sign up for this, had become my most ferocious protector and advocate. I owed it to him to do everything in my power to take on this disease, to fight it, and to make myself strong so I too could be there for him if and when he needed me. It was also the realization that as much as Peter was with me on this journey, I would need to take on that fight alone. No other person can be inside our minds and bodies and experience what we experience. It’s a cliché I know, but we come into this world alone and we leave this world alone. Love gives us the strength to make it through, but the ultimate strength to survive has to come from within.

When all five gurneys were stationed in front of their respective operating rooms, someone gave a final count and we were each wheeled into our surgery suites. Marveling at how choreographed everything appeared to be, I tried to give a little leg extension before shouting out, “This is just like a Busby Berkely musical!”

Once inside, I knew I would need to let go of any false sense of control and truly trust. I was introduced to several members of the surgical team including Ross Anderson, a medical engineer who had recently completed his Ph.D. at Stanford and had done work on an earlier version of the Medtronic Percept device which I was having implanted that day. That I can’t quite recall everyone’s name who was there that day is not a statement of their professionalism or compassion. From the moment everyone said hello to me and took the time to smile – the mask may cover it, but you can still see it in a person’s eyes – I knew I was in great hands.

While it’s true you are awake for much of the day, it’s also true that you are carefully sedated to avoid unpleasant things. For example, I asked for high sedation before the catheter was placed and, as of this writing, I am grateful not to have any recall of the experience.

Drilling

The anesthesiologist was keeping a close eye on me throughout the day and there was one period when I became especially agitated at the realization that the “crown” that had been attached to my head was also locked onto the table and I was unable to move my head (a good thing when one is having brain surgery!) Ivan was my advocate that day and helped me through that brief moment of panic. He also made sure my lips and tongue were kept moist and made sure a suction tube was ready should any postnasal drip sneak down my throat and cause swallowing difficulties or the sensation of choking. While many people came and went throughout the day, he was the one who was looking out for me from the moment the surgery started until I was back in my recovery room that night, and through the following two days, I was at the hospital. In DBS surgery as in life, we should all be blessed enough to have an advocate like Ivan.

About the drilling. In the pre-op overview of the surgery, they don’t evade the subject that seems to fascinate most people. What does it feel like to be awake while a surgeon is drilling into your skull? First of all, there is no pain. But, to be honest, the drilling sensation is quite freaky and loud; very loud! My perception of the time it took to drill the holes is starting to fade, but it seems to me that the drilling lasted several minutes. Since we were doing both sides of my brain, so it required drilling two burr holes and each burr hole required two episodes of drilling. While it was happening, Ivan was holding my right hand and Ross was holding my left. I squeezed their hands so tight that I was fearful I may have broken a finger.

Mapping

After the drilling, there was a period in which they continued the brain mapping and were actively listening to my brain. A few days ago, I emailed Dr. Sedrak to ask him if I was experiencing a false memory when I recalled someone in the operating room asking him to turn down the volume. While he didn’t necessarily confirm or deny that happened, he did say that they spent a lot of time listening to my brain and it was, indeed, very active. “A good thing!” he wrote back to me. As someone who has always had a hard time turning off my brain at night, it made a lot of sense. He also confirmed that the distinct memory of swooshing sounds like waves on a beach – my brain as an ocean?! – was common.

Implanting

The entire surgery lasted approximately eight hours because it was essentially three procedures in one – implanting the lead on the left side of my brain, implanting the lead on the right side of my brain, and placing the actual DBS device on my upper right side of my chest, just below the clavicle bone. I remember after they finished placing and testing the leads, Dr. Sedrak told me they were going to unscrew the uncomfortable big metal cage on my head – I had stopped thinking of it euphemistically as a crown long before – and then I would be able to go to sleep for the final part of the procedure. As the team slipped it off, I remember smiling, thanking them, and saying, “Yes, please. I just really want to sleep right now.”

Recovering

Recovering

As anyone who has surgery can tell you, waking up in the recovery room is truly a jarring experience. You are completely disoriented and, at least for me, I found myself trying to carry on small talk while I figured out what was happening. I have no perception of time from that moment on, but at some point, they wheeled me onto an elevator and up to a private room on the 5th floor of the neurosurgery center. I ordered food, meatloaf because the mashed potatoes it came with sounded good, but of course, I could only take one bite before feeling nauseous. A Physical Therapist had me walk around the hallway. Although I was very wobbly, I did it. She offered me a second round, and I said, “No thank you. I’m ready to lie down again.” Since the Delta variant was still a couple of weeks away from once again changing hospital rules, I was allowed only one visitor. When Peter came in, a huge feeling of relief washed over me.

Although I was expected to be released the following day, I was still very nauseous, physically weak, headachy, and had no appetite. Almost all of these symptoms were caused by the effects of the anesthesia and follow-up pain medications. A decision was made that I would spend an extra day in the hospital. I was visited by Ross who shared images he had captured of my brain waves during the surgery while the DBS was temporally activated. I remember Ivan coming in, changing my bandages, and everyone being pleased with how the surgical incisions (two on my scalp, one behind my right ear, and one on my right chest) looked. Dr. Sedrak also stopped by and asked me some questions to assess my level of cognition. Looking pleased with my answers, he said I was in the top 1% of patient recovery so soon after surgery. Another win!

Leaving

I was released after the second day and my physical recovery, including the healing of the surgical incisions, has surpassed expectations. I stopped taking the opioid-based pain medications almost immediately and, to no surprise, quickly began to feel better. I am staying busy around the house – reading, writing, doing small chores, hanging with our dogs and, of course, Pete and I are back to doing our daily three-mile walk. I do find myself getting fatigued quite easily and have had zero guilt about taking several small naps throughout the day. True to form, I’m getting anxious about missing work but our most excellent staff, under the leadership of our brilliant Operations Director and acting CEO, Steve Ferguson, is giving me the space and confidence to prepare for the next stage of this journey.

Powering

My DBS will officially be activated on August 17th and, as I type this with very stiff fingers and cramped hands, and a twisting right foot, I am counting the hours. Some people experience a placebo effect following the implant of their DBS brain leads and seem to have a remarkable decrease in symptoms. Doctors think this may be related to the post-surgical swelling and I did, indeed, have a couple of days of mostly symptom-free recovery. But three weeks post-surgery, that placebo effect is long gone.

I am nervous and excited about what my life will be like after the device is activated. I am also being careful about managing my expectations. I know, for example, that some of the more pernicious and less-visible symptoms that challenge me – problems swallowing, my eyes not opening in the morning unless I physically use my hands to pry them open, vocal challenges, a frozen and less expressive face – will most likely not be mitigated by the procedure. I understand that DBS does not stop the progression of the disease and, should it get turned off in the future, the symptoms that are relieved will most likely return with a vengeance. Finally, I know that it can take several months of trial and error to get the device programmed at the right levels. Still, if this does nothing more than reducing the severity and chronic nature of my Dystonia over time, that alone will make it all worthwhile.

One very clear memory from the surgery gives me great comfort. One of the main reasons patients are usually conscious during the surgery is so the surgical team can test where the leads are placed. Figuring out that placement is a million-dollar question and can dramatically impact the outcome of the surgery. That’s the art of the surgery and the sophistication in placement explains the advances that have been made in DBS over the years.

To help find the perfect placement for me, a movement disorder specialist joined the surgical team toward the end of the procedure. With the device temporarily activated, she put me through a series of tests to assess how I moved my legs, arms, fingers, etc. I remember her initially commenting on my left leg and how incredibly stiff and “dystonic” it was. I said to her, “My left leg is actually my good leg!”

As they played with the various levels of the device, she continued to manipulate that stiff and stubborn left leg. And then, finding that sweet spot, she said the magic words, “Ahhh … there it is. Do you feel that? Your leg is moving through the air. It’s like the dystonia is melting away.”

Living

I can clearly remember the elation from everyone on the surgical team. I wanted to jump off the surgical table and give them all a high-five but, of course, that would have to wait. In the meantime, I was given a great gift that got me through the rest of the surgery, the initial recovery, and the subsequent weeks at home. And I have no doubt it will be the same gift that will sustain me through the weeks, months, and years still to come.

Hope.

__________

A nationally recognized leader in the nonprofit sector, John L. Lipp has served as a trainer and keynote speaker for audiences around the world. He currently serves as CEO of Friends of the Alameda Animal Shelter. John’s publications range The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Recruiting and Managing Volunteers (2009, Alpha/Penguin) to creator of The Monsters Anonymous Club series for young readers, to personal essays for The Coffeelicious on Medium. In recognition of his lifelong commitment to a more humane world for people and animals, he was the recipient of the San Francisco Shanti Project’s 2019 “Dede Wilsey Champion of the Human-Animal Bond Award.” John and husband, Peter, share their Bay Area home with two wonderful rescue dogs, Lucy and Chance. He was diagnosed with Parkinson’ at the age of 49 in 2016. Follow John on twitter @VolunCheer.