Hiding

It’s the spring of 2017. I watch my enviably bright colleague arrive with a couple of associates; they enter the main conference room and he walks toward me as the others take seats on the far side of the large square table. A few more of my professional peers will soon trickle into the meeting.

We are twelve senior administrators from various colleges and schools of The University of Texas at Austin, and we meet several times each year to discuss collaboration in our work. This is our first meeting since my Parkinson’s diagnosis a few months earlier, and no one in my professional life knows about it.

Hardly anyone at all knows.

Placing his phone and small notebook on the table, my colleague sits down beside me while I try to locate the sweet spot in an uncomfortable chair. We greet each other and exchange pleasantries, as we have done many times before, and we engage in small talk while waiting for the rest of our group to arrive.

As he speaks, my stomach begins tossing my lunch from one side to the other. My heart beats faster. I feel clammy and it becomes harder to breathe as my internal monologue begins.

Can he tell I have Parkinson’s?

Is his smile one of pity?

Does he assume I’m less effective in my job?

Is he already taking me less seriously?

As an accomplished neurologist, he must know about my condition…can probably spot Parkinson’s a mile away.

He remains cordial and keeps talking.

I’m so sorry you’ve got it, but your secret is safe with me, I imagine him thinking.

The rest of our associates arrive and the meeting begins, but I have little recollection of it. For nearly two hours, choppy waves roll through my body. At times, the room blurs and its walls encroach. Hearing the conversation, but not absorbing anything, I remain silent, pretending to take notes and occasionally nodding in agreement.

I hoping I can keep playing along.

Tucking my twitchy left index finger under my leg, I try to will myself into participating. The large clock on the wall inches along. Time could not care less about my discomfort.

Just before the meeting ends, my neurologist colleague takes a phone call and leaves the room. My pulse slows and my breathing relaxes a bit. The room begins to feel bigger. One colleague speaks about next steps before we meet again.

I look at the calendar on my phone and begin counting the days.

Risking

Nearly three years later, I am out of the Parkinson’s closet, managing my disease, living my life, and, yes, doing my job. Nothing has changed professionally, although having a progressive disease means acknowledging that change always looms.

What has changed is that I recognize what was happening at that meeting. I now understand better the roots of my paralyzing fear. It had foremost to do with the threat of losing my identity as a healthy person and soon thereafter losing my professional standing. I bristled at the possibility of being perceived as ill and as “less than” I was before; I recoiled at the prospect of pity from and dismissal by others.

Of course, many people would have similar fears.

But here’s what else I now recognize. Because I feared perceiving myself in these ways, I attributed the same perceptions to others. Whether having to do with illness or with most any other life experience, we tend to make assumptions about what others think and feel, about all kinds of matters but especially about us; and frequently these prove merely to be our own assumptions about ourselves. In psychological terms, we call this a projection.

A fear of losing our identity and status is legitimate; it’s risky to live out loud with any chronic condition, not only socially but also professionally. Both subtle and overt discrimination may occur. Moreover, a fear of losing key parts of ourselves jars us from comforts we grow accustomed to and, perhaps, take for granted. I’m thinking of the comforts of the familiar and of feeling accepted among our most cherished groups of people and in our most coveted spaces.

Maya Angelou recognized this common human need to feel accepted, observing that, “The ache for home lives in all of us. The safe place where we can go as we are and not be questioned.”[1]

I’m learning that having a chronic illness spurs my aching for home precisely because it disrupts my safe places. But it also shows me that these safe places may be found precisely where I am already—among family, friends, neighbors, and colleagues, most of whom accept and even root for me—and that my foremost challenge may be to accept and root for myself.

_______

[1] Maya Angelou, All God’s Children Need Traveling Shoes

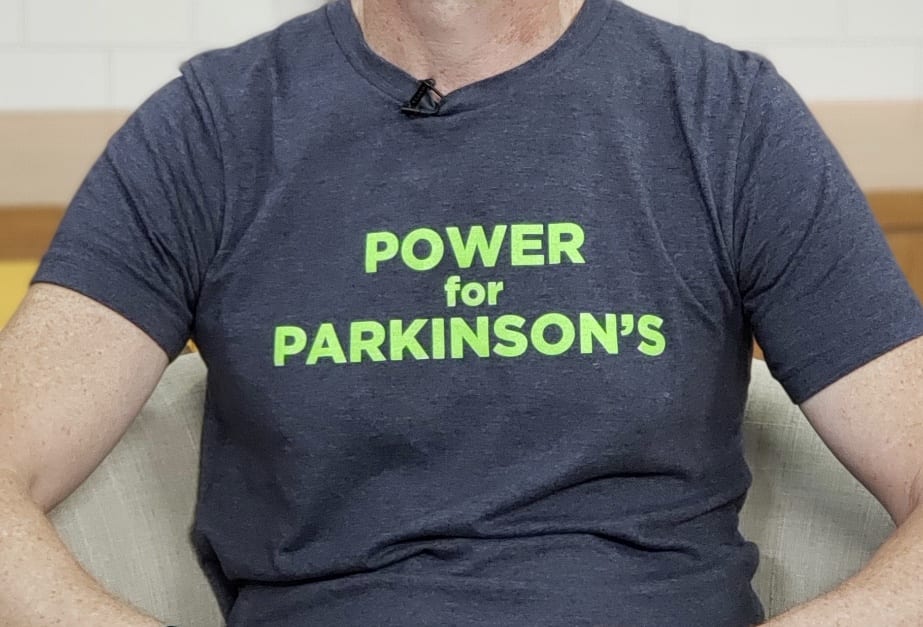

Photo: Lauren Halpern Public Relations

Allan Cole is a professor in The Steve Hicks School of Social Work at The University of Texas at Austin. Diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2016, at the age of 48, he serves on the Board of Directors at Power for Parkinson’s, a non-profit organization that provides free exercise, dance, and singing classes for people living with Parkinson’s disease in Central Texas, and globally via instructional videos. He also serves as a Community Advocate for ParkinsonsDisease.net, writing columns about living well with Parkinson’s. He is author or editor of 10 books on a range of topics related to bereavement, anxiety, and spirituality. Currently, he is writing a book on counseling people with Parkinson’s disease, which will be published by Oxford University Press.

Follow him on Twitter @PDWiseBlog