Everybody, as a child, wanted to be someone growing up, right? I wanted to be a marine biologist like Jacques Cousteau and sail the seas conserving marine life. I saw myself diving with exotic species and documenting the environment but circumstances conspired against me.

Parkinson’s, in its wisdom, chose me.

I have now entered my 43rd year with PD, having been diagnosed at age 7, and I am in a unique position to be able to pass on my experience and knowledge, not only of living with Parkinson’s but also of the communication difficulties people with Parkinson’s face on a daily basis.

But note, these difficulties have not stopped me from speaking and sharing my experiences with others, as I’ll detail.

Parkinson’s disease can affect every aspect of my daily life, from getting up in the morning, to staggering to the bathroom, to trying not to fall over whilst in the shower, to undressing and trying not to fall over as I take my socks off as I go to bed.

I regularly cut myself shaving, and I fall off the bed whilst getting dressed, believe it or not; even ‘stepping’ into a pair of underpants presents real issues and I’ve found myself rolling on to the floor…one leg in and one leg out! Not very dignified but rather amusing to watch according to my wife!

Once in the kitchen I regularly find myself spilling milk and sometimes the whole drink all over the work surface. Doing up shoelaces is a nightmare, and trying to eat sometimes just becomes impossible as I cannot get the food onto the cutlery to put it in my mouth, and even if I do, getting the cutlery actually anywhere near my mouth is a challenge.

All of these are everyday tasks that people take for granted…just like speaking.

How it All Began

My earliest memories of what I was later to learn was Parkinson’s was my loss of balance and the spasticity in one arm, which looked like I was part T-Rex! I kept falling backwards in my school assembly and I found that during my swimming lessons my legs would sink and I would almost be trying to swim whilst in a standing position. I used to stand on one leg while my mother cut my toenails, and one day I couldn’t balance and she kept shouting at me and slapping me in frustration. I started crying, not because it hurt but because I didn’t know why I couldn’t stand still.

And my dad and godfather used to shout at me when I was playing rugby because I couldn’t keep up with the other lads, thinking I wasn’t trying.

At this stage my speech wasn’t an issue, although to my mother and father, who already had me down, even at this early stage in my school career, as a high flying lawyer, thought my Northern accent most definitely was and issue! I had to learn to enunciate properly, and as a result I was enrolled at a speech and drama school to rid me of this Northern Curse.

I was forced to learn and recite poetry by heart and was entered into speech and drama festivals all over the North West of England. As I was unable to stand and recite the poems, I sat down on a chair in front of an expectant audience and then waited as the judges passed their verdict. I guess it was like Britain’s Got Talent but without Simon Cowell and the phone vote.

I was reasonably successful and my crowning moment was when I won a trophy for my interpretation of “Noah and the Rabbit” by Hugh Chesterman.

“No land” said Noah,

“There–is—not—any—land.

Oh, Rabbit, Rabbit, can’t you understand?”

But Rabbit shook his head:

“Say it again” he said;

“And slowly, please.

No good brown earth for burrows,

And no trees;

No wastes where vetch and rabbit-parsley grows,

No brakes, no bushes, and no turnip rows,

No holt, no upland, meadowland or weald,

No tangled hedgerow and no playtime field?”

“No land at all – just water,” Noah replied,

And Rabbit sighed.

“For always, Noah?” he whispered, “will there be

Nothing henceforth for ever but the sea?

Or will there come a day

When the green earth will call me back to play?”

Noah bowed his head:

“Some day…some day,” he said.

Incidentally, I also won our local Jubilee talent competition in 1977, much to my elder sister’s disgust, who was convinced her guitar duet was worthy of first prize.

When I wasn’t learning my poems I was usually in hospital, as the medical staff struggled to identify the strange symptoms I was exhibiting. Monday to Friday I spent on the ward being tested and assessed, and on the weekends I was allowed home.

A breakthrough in communication on my part came after visiting a doctor at the Manchester Royal Infirmary. He offered me 50p if I agreed to try a particular medication. Now he was talking my language! I agreed, and quickly stuffed the coin into my pocket.

The medication I was prescribed was L-dopa, Sinemet, a drug proven to help elderly patients cope with the onset of Parkinson’s disease.

It worked to an extent, but as I entered my teens I was referred away from the safety net that I had gotten used to at Booth Hall to a hospital in London that specialised in Movement Disorders.

Under the specialist care of Professor David Marsden and subsequently Professor Niall Quinn, I became the patient of choice in teaching seminars which included invited doctors and students from all over the world. I knew the drill, I knew the questions they were going to ask, and I knew the tests they would perform. I actually felt quite smug and wore a huge grin during these seminars, happy in the knowledge that I knew more than them about my condition, that I was the expert.

Voice Challenges

Over the years I have tried many different meds with a variety of success. I tried an intravenous apomorphine pump, which I had to come off as it caused embarrassing Viagra-like symptoms and extreme startle when I heard a telephone ring, which usually made me throw my drink or food all over myself and was clearly not ideal in my telesales work environment.

It was during my time working in telesales that I first noticed real issues with my voice.

Hardly surprising, really, as I was supposed to make more than 100 phone calls a day.

My voice became gravelly and sounded like I had a permanently sore throat. I was eventually diagnosed with laryngeal dystonia and treated with Botox in 1996.

I was 28 years old.

I was always a happy person to the outside world. “Here’s Matt. He’s amazing. All the things he has to put up with and he never complains.”

But inside I was getting fed up. Not only was I struggling to walk but the thought of not being able to communicate properly led me to self-harm. I cut crosses into my arm with my Swiss army knife. I blackened my own eye. It felt good and it fulfilled a need to punish myself, to blame myself; it wasn’t anybody else’s fault, after all.

Surprisingly I often did this when I was lying on my bed in an off state, un-medicated, that is.

I never hid what I had done from anyone. I usually just blamed falling over and hitting the side of my face. Why not? I often fell over, it was old news. Nobody suspected I had hurt myself deliberately.

But apart from being called stupid by another punter in the pub, nobody noticed or said anything to me. I actually didn’t care. This destructive behaviour continued, well the black eyes anyway. Cutting myself hurt too much, and it would leave permanent reminders of my mood, which I didn’t want.

Back to Botox. The trip down to London every five to six months, and the mere thought that enough poison to paralyse 2 ½ mice was going to be injected into my vocal cords, filled me full of dread.

The results, however, were awesome; and after the Botox had settled my voice was silky smooth. Note that before it did settle, it went through a rather cool Barry White-esque soul kind of sound, which my then girlfriend found rather alluring. But she dumped me in the end because she said my Parkinson’s pissed her off.

Six years on….

Deep Brain Stimulation

In 2004, aged 34 and with the amount of medications still rising and other options exhausted, the possibility of having deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery was discussed. This was a big deal. The surgery was fairly new and ground breaking at that time, but I trusted my specialist, Dr. Tom Foltynie, and his team implicitly. Such was the relationship we had built up over my then 20 years of attending the hospital.

The surgery was a success and its effects were life-changing. I was now able to get up in the middle of the night and go to the bathroom without crawling on the floor and weeing in a pot. It gave me my dignity back! I was able to eat without being unable to move 30 minutes later.

I have since become a brain stimulation advocate for Medtronic, speaking to patients considering the surgery to help them make an informed choice of their own. Last December, I flew to Morges, in Switzerland, to tell my story to over 750 employees at Medronic’s European holiday event.

I continued to have speech therapy on and off and also had the Botox injections until 2010. Remarkably, I found my voice was becoming resilient for longer and I went 18 months without requiring any form of treatment. My job no longer required me to make so many calls and perhaps it was the fact that I could rest my voice that helped it repair itself. I was finally discharged from the ENT Clinic and I haven’t been back since!

It was following my DBS surgery that I began to become more and more involved in raising awareness of Parkinson’s, particularly in younger people, and this in turn has led to numerous media opportunities, mainly through Parkinson’s UK and their press office and through the Cure Parkinson’s Trust.

I am now employed by the 2018 Healthcare Comms Agency of the Year, Havas Lynx in Manchester, and this has led to lots of speaking engagements all over Europe: Berlin, Brussels, Amsterdam, London, and Manchester.

Tips for Communicating

Here are two pieces of advice I can offer.

Use Dragon Software for voice recognition purposes on your computer. I use a head set at work if I am dyskinetic or unable to use a keyboard. Using it makes life so much easier.

Most important, keep smiling and engage with others. You’ll be amazed that while you thought you were a timid mouse you’re actually a tiger!

***

Noah and the Rabbit

by Matt Eagles

“No Parkies” said Noah,

“There—is—not—any—Parkies.

Oh, Rabbit, Rabbit, can’t you understand?”

But Rabbit shook his head:

“Say it again” he said;

“And slowly, please.

No tremors and no stiffness

And no apathy

No spillages, no anxiety and no sleepless nights

No staggering, no falling over and no pain

No masked expressions and laboured speech

No, walking sticks, wheelchairs, or bathroom aids?”

“No Parkies at all—just happiness,” Noah replied,

And Rabbit sighed.

“For always, Noah?” he whispered, “will there be

a day when there is a cure for Parkies?

And will there come a day

When the green earth will call me back to play?”

Noah bowed his head:

“Some day…some day,” he said.

_____

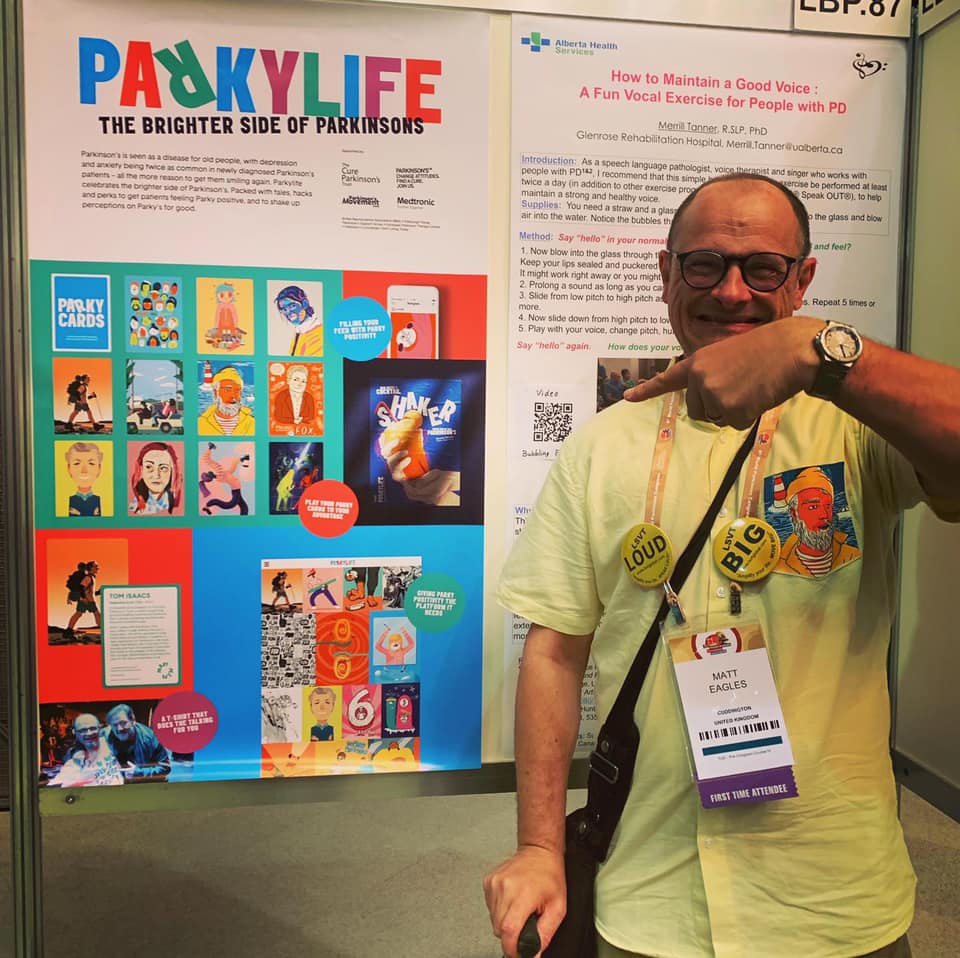

Matt is the creator and curator of ParkyLife.com, which shares “uplifting stories, clever hacks & positive thinking from Parky people.” Diagnosed 1977 and a positivity activist, he is Head of Patient Engagement at Havas Lynx Group.

Twitter: @MattEagles