At 2:41 on a Friday afternoon in 2018, I was strolling through my office, perfectly healthy, and had a stroke. It was a hemorrhage that required emergency, life-saving brain surgery, and it took away the use of my dominant hand, control of my right leg, and my balance. I was 50.

Recently, after nearly four years in this new life, someone asked me whether I would wave away the stroke or choose to keep it if I had a magic wand. Inherent in the question was the thought that perhaps the experiences in the interim were so rich that they had become a treasured part of my identity. Perhaps I would feel, as some deaf folks do, that this is core to who I am, that I’m now in the stroke “community” as if analogous to the deaf community, or that I’m not really disabled at all, but simply “differently-abled,” as is so fashionable to say for virtually anything nowadays.

I answered, “Umm, no stroke, please. Next question.”

In fairness, it is an interesting question and one I had pondered many times. After all, I did gain some significant things in the process of this health catastrophe: 1. Great parking. That can’t be overstated. 2. The friends I made in rehab. 3. The moments of closeness with old friends the crisis precipitated. 4. A book I was able to write about the experience. And 5. Greater license to decline things I don’t want to do. Without the stroke, all of these and more would instantly vanish.

On the other hand, about 100,000 things I could do again would be pretty great. I could clap my hands at the end of a performance instead of slapping my thigh with my left hand. I could jog across a room or at least hurry across it. I could sign my name in less than 30 seconds. I could drive any car I wanted and not just one that had been customized with a left-foot accelerator. I once again could play Jerry Reed’s “Stump Water” on the guitar and any of the hundreds of other songs I had learned to play over 35 years. And on and on and on.

But, as I told the gentleman who asked, this is just a parlor game, about as practical a way to spend time as arguing over which superpower would win in a fight — levitation or invisibility? What’s done is done.

The *real question—the *actionable question—is: How can I maximize the blessings that are within this curse? Here’s what I mean.

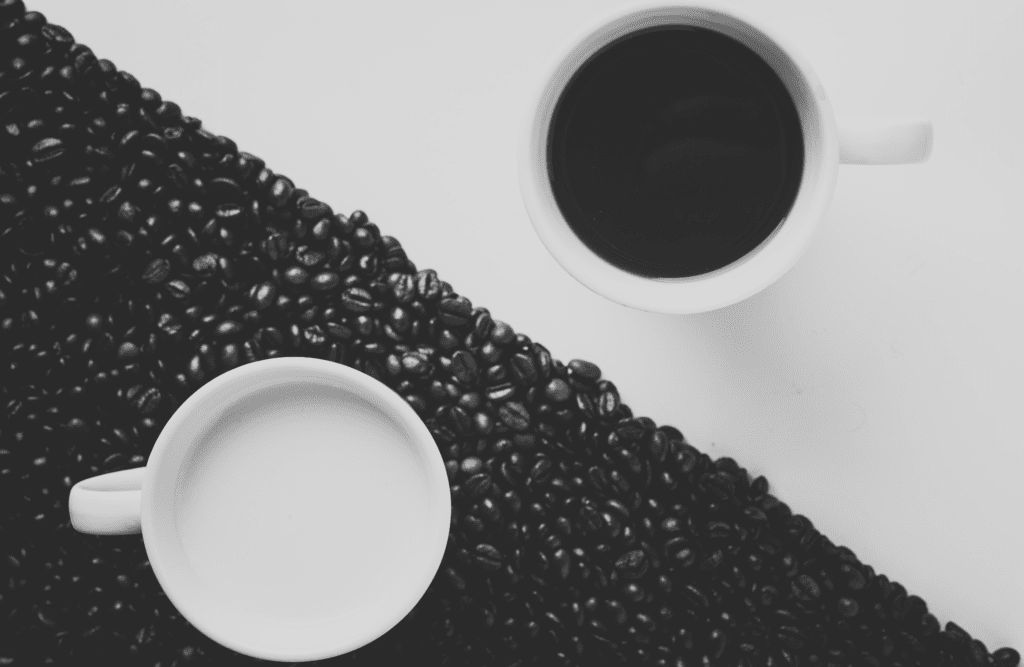

Think of the symbol of yin-yang. The symbol is half black and half white, but each paisley-shaped half contains within it a dot of its opposite. In this example, if we think of the black portion as disease (or in my case, injury) and the white portion as blessings in your life, then that white dot surrounded by the black paisley is what I need to focus on expanding. How do I make that white dot as big as it can be?

The stroke took away my ability to play guitar normally, something that was so important to me and such a big piece of my identity. But after a few months of mourning that huge loss, I picked up the guitar again and realized that I could play quite a lot with only my left hand. This eventually led to a feature story on NPR’s “All Things Considered.” Black paisley—loss of picking hand; white dot—“All Things Considered.” Black paisley—I can only type with my left hand; white dot—this fact led to a published book. The stroke took away my ability to have long, strenuous outdoor adventures by myself; but the necessity of having a good friend go with me made my multi-day kayak trip down the Nueces River a richer experience than it would have been solo. Black paisley, white dot.

It’s impossible to see all of these tradeoffs in the moment, but somehow it helps to know that they are there.

__________

Photo by Alex Padurariu on Unsplash

Avrel Seale is the author of 10 books, including With One Hand Tied behind My Brain: A Memoir of Life after Stroke. He lives with his wife and three sons in Austin, Texas. His next book, awaiting publication, recounts the above-mentioned trip down the Nueces River in South Texas.

Avrel Seale is the author of 10 books, including With One Hand Tied behind My Brain: A Memoir of Life after Stroke. He lives with his wife and three sons in Austin, Texas. His next book, awaiting publication, recounts the above-mentioned trip down the Nueces River in South Texas.