Background Information

Background Information

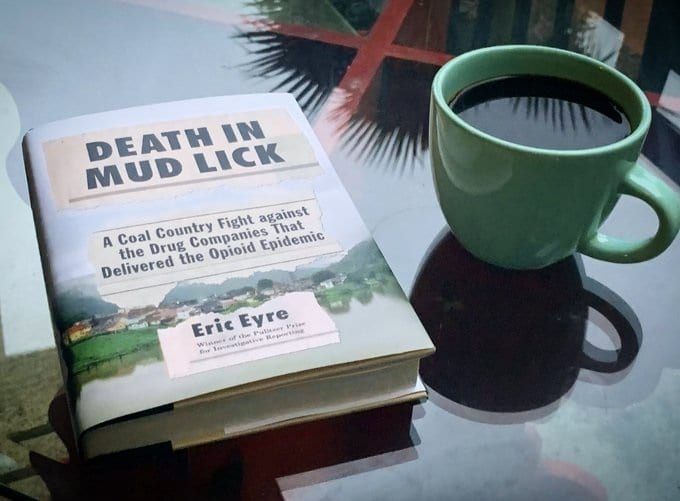

Eric Eyre was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in July of 2016, at the age of 51. Shortly thereafter, he was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting on the opioid crisis in West Virginia. Eric worked most recently for the Charleston Gazette-Mail. He is the author of Death in Mud Lick: A Coal Country Fight against the Drug Companies That Delivered the Opiod Epidemic (read an excerpt below).

Eyre’s work has won several additional national awards, including the Investigative Reporters & Editors (IRE) Medal, Fred M. Hechinger Grand Prize in Education Reporting from the Education Writers Association, National Headliners Award, Society of American Business Editors and Writers award, Gerald Loeb Award for business writing, and an Association of Health Care Journalists award. He also was the recipient of a Kaiser Family Foundation fellowship. His investigative stories have mostly spotlighted issues in rural West Virginia communities. A native of Broad Axe, Pa., Eyre graduated from Loyola University of New Orleans and received a master’s degree from the University of South Florida while on a Poynter Fund Fellowship.

Eric’s interests include Rock Steady Boxing, tennis, Parkinson’s group exercise, and reading. He and his wife, parents to a son, live in Charleston, West Virginia.

Five Questions

How did your PD diagnosis come about?

Elbow pain and stiffness. Also some right foot dragging. An orthopedic surgeon ruled out tennis elbow or tendon damage. A neurologist performed an EMG (electromyography) and diagnosed me with PD based on my gait and early “frozen face.” I got a second and third opinion from movement disorder specialists. They confirmed.

What are the more significant challenges you face, and how do you meet these challenges?

Sleep, tremor in right hand and fingers, difficulty typing and writing, extreme stiffness. High-intensity exercise remains the best medicine. Also, I try to eliminate as many potential stressors as possible.

How do you cope with having PD?

Exercise, exercise, exercise. Eating healthy. I lean on others with PD for coping suggestions, how they solved PD-related issues. We share “notes.” I try to stay on top of the latest PD research/studies (though too much of this can wear you out). My motto is just keep going until God has to drag me across the finish line.

What has surprised you most about living with PD?

That it’s not just about the tremor. There’s increased anxiety, rigidity, sleep problems, slowed movement, less manual dexterity, back pain, and a host of other issues. On the plus side, I’ve met a whole new group of wonderful and supportive friends.

What wisdom would you offer someone who is newly diagnosed? Or, what would you want your newly diagnosed self to know about the journey ahead?

Realize that you’re not alone. Tell family and friends and work colleagues/bosses right away. Find a PD exercise class: boxing, spin, etc. Keep moving. Take long walks. Hit the treadmill and exercise bike. Sing, dance, swim, yoga, Tai-Chi. Make exercise your No. 1 priority each day.

***

Excerpt from Death in Mud Lick (pp. 132-135)

About a year earlier—or was it two years?—I noticed that my handwriting was suddenly getting smaller. My right foot started dragging. I had an unexplained cough, but only when I talked. And my right elbow—it just wouldn’t straighten out. It was stiff, locked in an L. I thought it was tennis elbow. By the summer of 2016, two months after the judge unsealed the state’s lawsuit against the distributors, I headed to an orthopedic surgeon—he had replaced my wife’s hip a year earlier—and he ordered up an X-ray, couldn’t find any tendon damage, and referred me to a neurologist. By the look on his face, I gathered something was wrong.

The neurologist hooked up a series of needlelike electrodes to my right arm. It was a Saturday morning. I was the only patient in the office. I was having an electromyography, or EMG. A machine shot bursts of electricity into my elbow. My arm twitched with each jolt. He was testing for nerve damage. I passed with flying colors. I figured I was in the clear; maybe a referral for some physical therapy for a strained elbow and I’d be on my way. But the neurologist started examining my face. Next he asked me to take a walk across the room. Only then did I realize he had used the EMG to rule out other possibilities.

“You probably have Parkinson’s,” he said, then handed me a prescription for a Parkinson’s disease treatment drug that’s also used to diagnose the disease. If it works successfully to lessen symptoms—such as stiffness and tremors—there’s a good bet you have it.

I didn’t want the drug to work. And it didn’t. At least after I stopped taking it. It gave me a metal-like smell in my head. I couldn’t sleep at night. My symptoms persisted. I started to research Parkinson’s on the Internet. I read through the common symptoms: small handwriting (known as micrographia), muscle stiffness, lost sense of smell, tremor, excessive sweating, loss of balance, uneven gait. I had them all except loss of smell.

I sent an email to the founder of the West Virginia Parkinson’s Support Network. George Manahan owned a marketing and public relations firm. We had found ourselves on opposite sides when my reporting prickled public officials. They would hire George’s firm to do damage control. But he wasn’t one to hold a grudge. George suggested that I tell my editors about my potential diagnosis right away. PD symptoms can make you look as if you were inebriated, he told me. I had some trouble walking. My wife, Lori, had noticed I slurred some words. I told the bosses. George also mentioned a new doctor at Marshall University’s hospital in Huntington. He had just completed his residency. He was a movement-disorder specialist, the only one in the state. I called for an appointment. I was in his examination room the next week. Lori drove.

Dr. Vikram Shivkumar put me through a battery of tests. I closed my eyes and counted the months of the year backward. I shuffled up and down the hallway. I tapped my fingers, one at a time, to my thumbs. I squeezed his hand. He typed something into the computer, then swiveled around on a stool to deliver the news. Only he started coughing. He was having a coughing fit.

“Excuse me, I need to get some water.” He left the room.

We waited.

He returned with a bottle of water, screwing the cap back on. “You definitely have Parkinson’s.”

Lori cried. I said nothing. It wasn’t a surprise. I had done the research, done the reporting. I knew this relentlessly progressive disease had no cure. In the short term, I could do physical therapy. I made an appointment the next day.

I seemed to be one of the few patients who wasn’t there to rehab a new knee or hip. I wore my work clothes—dress shirt and khakis. Jamie Tridico, the physical therapist and owner, guided me through a series of exercises with a heavy ball and elastic bands. It was like a mini-boot-camp. I was sweating. Next time, I would wear a T-shirt and shorts. As I left, Jamie handed me a flyer. It was for a boxing class, twice a week, ninety minutes each session. Boxing seemed counterintuitive. You’re going to hit people with a neurological disease upside the head? Wasn’t that the cause of Muhammad Ali’s Parkinson’s? I decided to give it a shot.

The gym was in the worst part of town, in a former warehouse, beside a drug detox center. Protective headgear, battle ropes, and knuckle tape were strewn about. Giant metal fans rumbled against the stifling heat. Dust and grime coated the cement floor. The gym smelled of dried sweat, vomit, and Pine-Sol. A makeshift ring with a plywood base was about four inches off the floor. It did have ropes. And corner buckles. Heavy bags of assorted colors, weights, and quality dangled on thick chains from metal girders that crisscrossed the ceiling. Someone handed me a pair of gloves.

About twenty of us there had Parkinson’s, men and women, ages thirty-seven to eighty-five. We lined up at the heavy bags. Jamie, who led the class, barked out the combinations: jab, cross, hook, uppercut; rapid-fire blows, body shots, knockout punches.

“Knock ’em out!” Jamie shouted. “Last round. Knock ’em out!”

An older woman, Ann, swatted at the bag, holding herself upright with a walker between rounds. Volunteers would lift you up if you fell down. After thirty minutes, I was gasping for air. After an hour, my eyes were bloodshot, my arms heavy, my legs wobbly. In my mind, Parkinson’s was unrelenting, like a raging fighter coming right at you, but in this gym, you could fight back. Intense physical exercise, short bursts of energy, helped delay the disease. I put my head down, gritted my teeth, and slammed the heavy bag.

__________

Photo: Bethany Barnes