Awake

It is becoming routine now that I wake at four in the morning. Rather than lying there, perturbed that I can’t get back to sleep, I have made this time of day a valuable one, an important part of my daily routine. I am able to enjoy a quiet rumination before the day begins. Everyone in the house is asleep but me. The dogs have yet to begin barking in righteous indignation that they haven’t yet been fed. It is my Springer Spaniel’s 13th birthday today. I can just barely hear his easy breathing as he sleeps on the floor next to me. My hearing aids are out, adding to the near silence. I am well back from the starting line of the tyranny of my daily to-do lists.

Significantly, I have yet to begin taking my twenty-some daily Parkinson’s pills.

Photos

My thoughts (and writing) this morning is of one of my forbearers. Yesterday, my oldest brother sent me a text of an old photo of our great grandfather, Steven Frank Smith. My generation knew him as “(Great) Grandpa Frank.’ He helped operate a silver mine in Central Idaho, near Idaho City. If it isn’t in the Frank Church Wilderness now, it would be nearby.

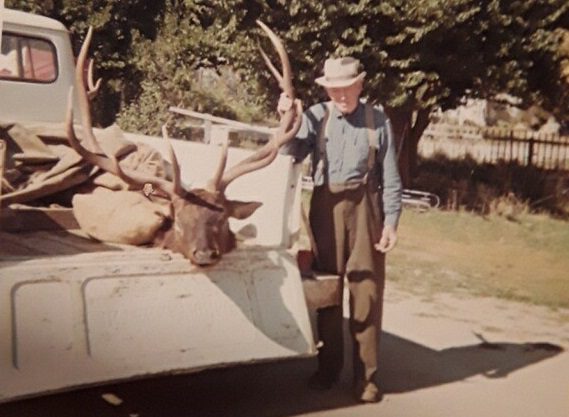

Often photos are dated somewhere along the edges, but this one isn’t. My thoughts about him, however, center on the “era” and the context of his life rather than his vital statistics. The photo shows the old man standing behind his dusty old pickup, one hand grasping a horn of a very large elk. The antlers seem to reach from one side of the pickup bed to the other. I wonder if he shot it above his hunting stance or below, as it would be hell to drag it uphill by himself, whole, no less get it into the bed of his pickup. He must have had help (perhaps the someone who took the photo?).

What makes fodder for this morning’s thoughts is his terse description of the photo subject, written on the back of it in pencil, “My last elk.”

Words

I am not much of a hunter, no less an elk hunter. My interest is the words. They could vary slightly, for example; “My last…..(fill in the blank).” Parkinson’s people keep the first two words handy as things change for us over time. They can fill in the blank with the latest thing one used to be able to do. “My last time I rowed a boat on a river… My last time I drove my car… The last time I walked without assistance…”

I wonder what he meant by those three words. I wonder what he knew then that we don’t now? In our world, it is uncomfortable not knowing. Not completely understanding. I have always thought good art, whether it be visual or written, beguiles the viewer with a chunk of mystery that keeps the viewer connected to it. Birth and Death are very clear words. It’s all the stuff in between that is confusing and mysterious. That’s a Parkinson’s world.

Whether in the pulpit or presiding at a funeral, over time I developed a strategy of pushing the boundary of death to and for a grieving audience, those looking to make sense of a loss of their loved one. One method I use to make war on the end of someone’s life is to hold up an old, yellowed obituary cut out of a newspaper. I still have several from my undergraduate years that my mother would send me when someone from our church died.

That little piece of paper, purporting to describe someone’s life in a two or three-inch column. I still have some of them, now very yellowed. On the other side would be a truncated piece of the column of the latest 4-H club news, or perhaps part of an ad for the latest model of a vacuum cleaner. Or whatever. The obit sort of survived, since it was whole, but only nonsensical parts on the other side survived, the latter forming a posterity of nothing.

Memory

In my tenure as a Presbyterian Parkinson’s Pastor, (my tongue twister years), I tried to work the tension between ‘“Life after death and nothing after death.”

I would then approach the idea in this way; “Is this all that’s left of this person’s legacy? This fragile, yellowed piece of newsprint?” Before COVID, I presided over two or three memorial services that filled the sanctuaries. “Look,” I would say, to all the people present that day, “Friends, take a moment and look around you! Look how many souls are here, seeking to remember beyond the little yellowed piece of newspaper!

When I say these words, in my heart’s memory, I am remembering Grandpa Frank’s photograph on a small piece of paper. His giant elk. On the back, the words, “my last elk.” Great Grandpa alive there, still transmitting the mystery meaning of sixty-some years ago.

“My last elk.”

__________

Gregory Tatman is a minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA) and a chaplain in an Oregon prison. He lives in West Linn, Oregon, with his wife, Judy, and enjoys building boats and playing the clarinet.