“Piglet sidled up to Pooh from behind.

“Pooh!” he whispered.

“Yes, Piglet?”

“Nothing,” said Piglet, taking Pooh’s paw. “I just wanted to be sure of you.”

A.A. Milne

Old Friends

It’s 1980, near the end of my 6th grade year, and my parents and I are leaving Plano, Texas, a budding suburb of Dallas where new housing developments spring-up like popcorn in the flat North Texas landscape.

A brisk, cool March breeze blows, making the flagpole outside Haggard Middle School clang.

I see my dad’s car parked at the curb, pointed toward Atlanta. He and my mom sit patiently in the front seat, allowing me the time I need to say my goodbyes after the day’s final school bell rang. In a few days, I will start at my new school.

I see Ryan and Tony, and we part quickly in the way 12-year-old boys do—saying something like, “Stay cool, Man” before they ride off on their BMX bikes doing wheelies down the street. Then, I see Craig and Clay, my next-door neighbor Staci, and a few others whose names I cannot recall. They wish me well and pledge to stay in touch but this is difficult in the days before email and the Internet .

Looking down the rows of bike racks, my eyes flit to the heavy sea of adolescent kids that now surrounds the school. I scan it for Tracy, my close friend since 4th grade. We often sit next to each other in class, get in trouble for talking at the wrong times, pass notes, and share homework answers. For her 10th birthday, I rode my bike to Zee’s Tees and picked-out a light blue hoodie and had a sparkling rainbow-colored decal ironed onto it. It’s the first time I remember saving my money to buy a gift for a friend. She wore the hoodie all the time.

Smart, interesting, and funny, Tracy is among the first people I recall feeling sure of as a friend.

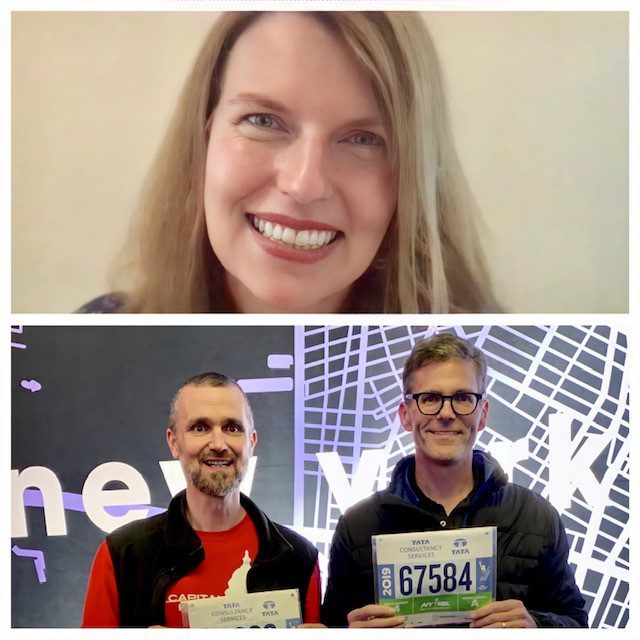

Now 40 years later, I think of all of this, and more, as I log-on to Zoom before speaking with her.

New Friends

Earlier that same day, I had a Zoom call with Ethan, one of my newer closest friends. He and I have Parkinson’s disease, and we met a couple of years ago through the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. When we get together, we talk about Parkinson’s, of course, and how we’re each doing—with meds, movement, sleep, and other challenges—but we also talk about running a next marathon together, politics, work, and our families—the kinds of things friends talk about because they’re meaningful and personal.

What Tracy and Ethan have in common are ties that bind; ties of friendship characterized by risk and trust, authenticity and openness, freedom and laughter; the ties that unite human beings in ways that enliven their souls and offer assurances that endure. These ties often begin in childhood, but they can form at any age. In fact, I count the friendships I have made with others on the Parkinson’s path—with people like Ethan—as one of the unexpected gifts this illness has offered me.

Henri Nouwen understood friendship more keenly than most. He writes, “When we honestly ask ourselves which persons in our lives mean the most to us, we often find that it is those who, instead of giving advice, solutions, or cures, have chosen rather to share our pain and touch our wounds with a warm and tender hand. The friend who can be silent with us in a moment of despair or confusion, who can stay with us in an hour of grief and bereavement, who can tolerate not knowing, not curing, not healing and face with us the reality of our powerlessness, that is a friend who cares.”[1]

Sure Friends

I think I have gotten better at friendship since Parkinson’s took-up residence in my brain. I have become more like I was in my childhood. Eager to share another’s struggles and willing to share my own. Comfortable in the difficulty of silence, ambiguity, and, yes, in some instances, my powerlessness. We have so much less control than we assume that we do. Parkinson’s teaches us this. In fact, thanks to Parkinson’s, like Milne’s Piglet, I am less enamored with control, and more comfortable with, and comforted by, merely reaching out to my friends for assurance, and with them reaching out to me.

Which reminds me, again, of Tracy.

In the 5th grade, at Tony’s house, my hand and arm accidentally went through a glass pane in a French door, which required many stitches and my missing a few days of school. Tracy made a card for me that said, “I’m sorry you cut your arm” and urged me to “Get back to school!” She rode her bike to my house with another friend and gave it to me with some candy.

The kind of thing a friend does, whether old or new.

My arm healed and I got back to school. The following year, I would make that drive with my parents to Atlanta and Tracy would move to Houston with her family. Many years passed before we reconnected, but it felt like we just picked up where we left off.

Even though he wasn’t there, I have a feeling Ethan will understand.

In fact, I’m sure of it.

For other thoughts on friendship, see:

A Time to Talk: Parkinson’s and Friendship, and

Parkinson’s and Friendship

__________

[1] Henri J. M. Nouwen, Out of Solitude (Notre Dame, IN: Ave Maria Press, 1974/2004), 38.

Allan Cole is a professor in The Steve Hicks School of Social Work at The University of Texas at Austin and, by courtesy, professor of psychiatry in the Dell Medical School. Diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2016, at the age of 48, he serves on the Board of Directors at Power for Parkinson’s, a non-profit organization that provides free exercise, dance, and singing classes for people living with Parkinson’s disease in Central Texas, and globally via instructional videos. He also serves as a Community Advocate for ParkinsonsDisease.net, writing columns about living well with Parkinson’s. He is author or editor of 10 books on a range of topics related to bereavement, anxiety, and spirituality. His latest book, on counseling people with Parkinson’s disease, will be published by Oxford University Press in 2021. Follow him on Twitter @PDWise.