The Sanctuary

The Sanctuary

It’s a Sunday morning in the summer of 2017, nearly a year since my diagnosis. Still living in the Parkinson’s closet, I push through most days feeling afraid and alone. Even with my family and several friends a few feet away, today is no different.

I sit silently in the sanctuary.

My wife Tracey, our daughters, Meredith and Holly, and I gravitated here a few months ago. This small community of people from nearly every continent and with nearly every skin tone offers open hearts and shares open minds. We are drawn to this church’s racial and ethnic diversity, and its commitments to social, economic, and environmental justice.

We are drawn to its conscience.

These folks extend hospitality to the poor, homeless, pilgrim, and stranger. Fortunately, they also welcome those trying to figure some things out.

The Journey

Sitting at the back of the sanctuary, as I typically do, I think about how I got here.

A distant cousin jarred my more or less placid religious quest when I was in the 6th grade. Embracing a fundamentalist flavor of Christianity, he scared the s^&% out of me with his talk of the Antichrist and pending doomsday scenarios, things like the rapture and Apocalypse, which I’d never heard of before but which he swore were clearly “prophesied” in the Bible. I was an Episcopalian, after all; and while I knew Rites I and II of the Holy Eucharist by heart, I had no clue what the Bible said or didn’t say.

I had to ask what prophesied meant.

Other than for that period, however, I mostly found comfort in my family’s religion and in church. There, I learned stories about Jesus, who treated people with compassion and healed them. I spent time with flawed human beings aiming to follow his example and latch-on to his hope. Churches were enchanted places that housed mystery and intrigue. They made me tingle and feel warm. I loved their smells and their people. In church, I experienced what the psychologist Erik H. Erikson called a sense of at-home-ness in the world.

Sometimes, I still do.

The Mosaic

Back to the congregation gathered here, they come with authenticity and vulnerability, with compassion and generosity. They come as those who struggle, hurt, and hope. Collectively, they come to learn about and live out the values of Jesus of Nazareth.

He taught and modeled these values, saying, “Blessed are the peacemakers,” (Matthew 5:9); “Whoever has two coats must share with anyone who has none; and whoever has food must do likewise” (Luke 3:11); and “you shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Matthew 22:39).

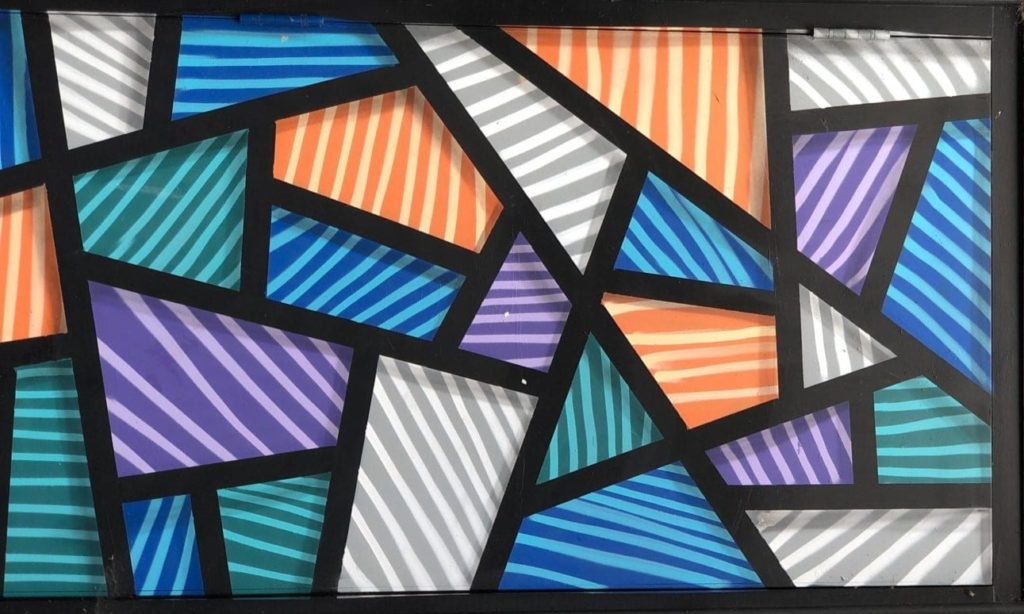

The clear day’s sun shines through the mosaic of stained glass that surrounds the triangular chancel. At certain moments, its colors pop out as if hoping to land in worshiper’s laps. A woman in her late 20s plays “Morning Has Broken” beautifully on her violin.

From the back of the sanctuary, I take all of this in.

My mind drifts to experiences of the past year: a faint tremor in my left index finger, an initial misdiagnosis, multiple exams, a brain scan, sleepless nights, worries, loneliness, and tears. Staring at the stained glass, I consider my mosaic of beliefs: about justice and mercy; fairness and equity; pain and comfort; meaning and purpose; despair and hope.

I also consider if I any longer sense a presence of the divine, whether in churches or in my life.

Wondering what life might require in the years to come, I look to my right, where Holly, Meredith, and Tracey sit, and fight back tears as my daughters draw in their sketchbooks.

A guitarist plays another musical piece while a trio sings along.

The Pilgrims

I look around the room, taking account of others who have come to church that day. Most are members who attend weekly. Many face the tensions of living a burdened and faithful life.

There’s Caleb, a sweet, interesting, and bright twelve-year-old boy with autism. He works valiantly each day to go to school, to interact peaceably with others, and to be a typical kid. Once, he invited Tracey over for dinner and the rest of us got to join her. His remarkable parents seated beside him, Sarah and Sam, tirelessly advocate for Caleb, model pure vulnerability coupled with exquisite courage and grace, and never cease cheering him on. All of us do.

There’s also Ruth, an older woman with a gentle disposition and astute mind whose medical condition has her confined to a wheelchair, and for whom living alone gets more and more challenging. She sits next to Nancy, who faithfully and tenderly cares for her friend, and whose political positions impress me.

Julio and Astrid are there as well. They will marry in a little over a year, and I think of Julio’s longtime separation from his family because of immigration concerns. They cannot get back into the U.S. from their native Mexico, in spite of having lived here for many years.

Then, I see Leslie, who lives courageously, with dignity, and at enviable peace with advancing breast cancer that has metastasized and spread. Her contagious, resolute smile simultaneously heartens and convicts me. Months later, she’ll be in hospice care.

I also see Jose, a kind and brawny man in his late 30s, surrounded by his lovely parents as well as by his siblings, nieces, and nephews. All of them, along with the larger church community, have prayed for Jose while he sought sobriety and spent nearly a decade in prison. He’s recently been released and hopes to get his life back on track.

I then flashback to Kate, a middle-aged woman who lives on the streets. She wandered into the church a couple of weeks earlier and we met in front of the large coffee urn. Her clean white coffee cup stood in stark contrast to her dirty fingernails and the dinge of homelessness that covered her. She heard voices and seemed scared and suspicious. Like many of us, she was there looking for connection, significance, and hope.

The Sacred

Life is not easy.

We get sick, lose those we love, struggle for meaning, seek after peace, and clamor for justice. These days, we also worry about pandemics and crushing need on a global scale. We experience a lot of adversity.

Surrounded by all of this, and more, we desire to have a place in communities that value us, reassure us, companion us, and urge us on. Perhaps as we also long for clues of a divine presence in our lives.

If not now, eventually. It has always been this way. It’s the human condition.

I’ve spent much of my life looking for answers to the big life questions, religious and otherwise. For decades I searched mostly in books, whether when reading them or writing them, and by sorting through the ideas and insights of the sages.

Now, I’m more apt to look for answers, or at least possibilities, in people and relationships, in shared struggles as well as joys, in those who stand in solidarity against any form of injustice and dedicate themselves to creating something better.

Really, I hone in on where I see efforts within a community to love, to be loved, and, as the Bible says, “to share one another’s burdens.” (Galatians 6:2).

You can learn a lot sitting in the back of a sanctuary.

Sometimes, you can even catch a glimpse of the divine.

__________

Photo by João Ferrão on Unsplash

Allan Cole is a professor in The Steve Hicks School of Social Work at The University of Texas at Austin and, by courtesy, professor of psychiatry in the Dell Medical School. Diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2016, at the age of 48, he serves on the Board of Directors at Power for Parkinson’s, a non-profit organization that provides free exercise, dance, and singing classes for people living with Parkinson’s disease in Central Texas, and globally via instructional videos. He also serves as a Community Advocate for ParkinsonsDisease.net, writing columns about living well with Parkinson’s. He is author or editor of 10 books on a range of topics related to bereavement, anxiety, and spirituality. Currently, he is writing a book on counseling people with Parkinson’s disease, which will be published by Oxford University Press. Follow him on Twitter @PDWise