What Do You See?

About a year after my diagnosis with Parkinson’s disease, I discovered the work of the British philosopher Havi Carel, who lives with a chronic and progressive lung condition, and who points out the importance of distinguishing illness from disease.

When we focus on disease, we tend to look at a person objectively, at a distance, and primarily in terms of the physical body and its dysfunction.[1] We hone in on what is wrong with hearts, or lungs, or brains, with vital organs and systems, and we linger on how medicine may help them work better and more efficiently.

Contrast this view with a focus on illness, which attends to the subjective, so what, questions of disease.[2] As Carel notes, “Illness is the experience of disease, the ‘what it is like’ qualitative dimension as it is experienced and made meaningful by the ill person.”[3] In practical terms, viewing Parkinson’s principally as an illness helps me hone in on the colors and contours of what my life is like, day to day, moment to moment.

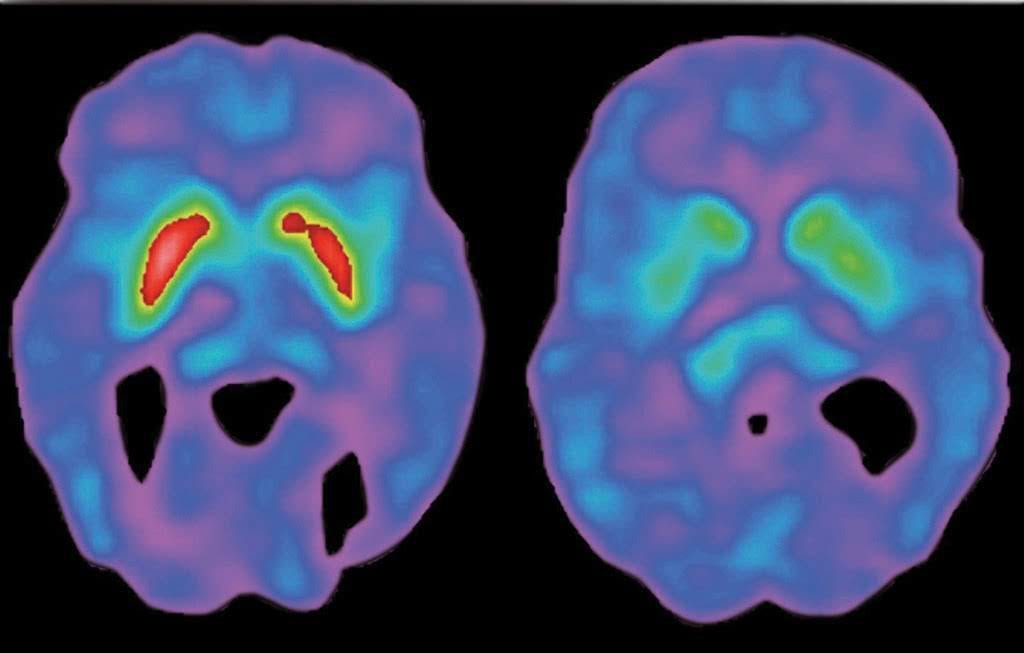

The objective body and facts of disease certainly have their place in medicine. Like when I got a DaTscan to confirm a Parkinson’s diagnosis.

Disease

The barely-lit room looks as cold as it feels. I lie down on a hard table that becomes the bottom half of a tube that covers most of my head and shoulders. About 15 feet away, a technician who greeted me as I entered the room sits at a small control board. I can barely see his face as he explains the DaTscan procedure; neurologists sometimes order this scan as a way to help confirm a Parkinson’s diagnosis. It’s difficult to hear him due to the hum of a fan blowing fresh air, presumably to keep the imaging equipment cool. His shadowy silhouette, whose every third or fourth word I understand, reminds me of a Peanuts character: blah, blah, imaging, blah, blah, blah, dopamine receptors, blah, blah, blah, blah relax…

He tells me what I already know. After reading about DaTscans, I have learned that this procedure provides an image of dopamine transporter activity in the brain. Particular patterns of activity are indicative of Parkinson’s.

“Any questions?” he says.

“How long does my head have to stay clamped in this position?” I say.

“Usually it’s about 45 minutes,” he says, pushing a few additional buttons.

He pauses.

“Any more questions?”

“This isn’t your first rodeo, is it?” I say.

Silence.

“OK, here we go,” he says.

The scan starts, and for what seems like an hour the camera tube moves around my head in strange patterns. A gear-y whine joins the white noise of the cooling fan. I have goosebumps on my skin.

Finally, the camera stops moving and the whine quiets so that only the sound of the fan remains. The room lightens and peripherally I see the tech approaching the table where I lay. My scalp burns, my head throbs. I’m still woozy from a sedative a nurse gave me earlier, and the tech helps me stand and walks me back to the same room I was in earlier, where I lie down with a thin blanket hoping to get warm.

Half an hour later, the same tech returns to walk me outside to the parking lot, where Tracey is waiting for me. When I get to the car’s passenger door, he opens it, looks at me, and says, “Good luck.”

This is what it’s like to have someone see and treat your disease.

Don’t get me wrong, I care about dopamine transporter activity; but only because a lack of it makes me feel poorly or prevents me from doing certain things I value. Otherwise, who thinks about how much dopamine activity you have going on in your brain?

But I care about other things, too, like when I’m seen as a whole person in relation to a disease that has come into my life. I want my doctor to attend to my illness, not just my disease.

Illness

A week after my scan, my wife Tracey and I walk into my neurologist’s office together, just as he’d asked us to do. This place looks different from when I first saw it: a little brighter and warmer, smaller and less like a maze. A friendly receptionist immediately invites us back to the same exam room where my life changed just four weeks earlier. We take a seat in chairs next to the small desk where I first showed Dr. T my labored handwriting. He is the one who ordered my DaTscan.

After only a minute or two, Dr. T enters the room wearing a colorful bowtie, wire-rimmed glasses, and a burnt orange lanyard with The University of Texas written on it that holds his St. David’s Medical Center ID badge. He says “good morning” as I stand up, and we shake hands. He also extends his hand to Tracey and introduces himself to her.

“How are you two doing?” he asks.

“I think we’re ok,” I say, “Taking one day at a time…learning how to live with the new family member.”

He’d offered this image of “the new family member who will always live with you” to describe Parkinson’s.

He flashes a compassionate smile.

He then asks about my symptoms and how I’m doing with the Azilect, the medicine he’d given me. I tell him I seem to be tolerating it just fine and that I think it’s helping with the stiffness.

He nods.

“Well, I suspect you have some questions,” he says.

I pull out an index card with questions I’ve prepared, and for nearly 30 minutes I ask him about Parkinson’s disease. I want to hear about the rate of disease progression and the different kinds of medicine he envisions me taking. I also ask him about resources for support in the Austin community. Of course, I’ve already researched all of these questions, but I’m entrusting my neurological life to this man. I need him to weigh in.

I need him to invest, too.

He restates being confident about the disease progressing slowly, and when I ask about “falling off a cliff” with the disease, meaning I want to know if it will progress slowly with subtle changes for a period, but then accelerate and push me into a rapid decline, he assures me it will not. “It doesn’t work that way. There are never any 100% guarantees, of course, but I think you’re going to do well for a long time.”

Tracey smiles, and places her hand on my back.

“I think so, too,” she says.

He then shares his thinking about medications, including drugs that stimulate dopamine receptors (agonists) and replace depleted dopamine (carbidopa and levodopa) in your brain, and he touches briefly on a surgical procedure called Deep Brain Stimulation, or DBS. It’s remarkably effective at relieving symptoms and its technology is getting better all the time; but DBS tends to be what you opt for when medicines become less effective. He also mentions two local organizations for which he has a high regard, Capital Area Parkinson’s Society and Power for Parkinson’s, which provides free exercise classes, and he encourages me to explore their offerings.

I tell him I will.

Seeing that I have no other questions, he looks over at Tracey.

“What questions do you have?”

She looks at me.

“He thinks I’m in denial, but, like you, I really believe he’s going to do well. He’s a fighter, and a good patient.”

I put my arm around her.

“Just take good care of him. We need him.” Her voice cracks slightly.

Dr. T flashes another kind smile.

“I will. He’s going to do well.”

Tracey pulls a bag of cookies from her purse and gives them to him—her chocolate biscotti. She’s a professional baker.

“You want to make sure he’s taken good care of,” he says.

“You’ve got that right!” she says.

We say our goodbyes and leave his office.

Driving home, our new family member seems a little less intrusive, and I feel a little more human.

Like I’ve been seen.

__________

[1] Havi Carel, Phenomenology of Illness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 15.

[2] ibid, 46.

[3] ibid, 17.

Allan Cole is a professor in The Steve Hicks School of Social Work at The University of Texas at Austin and, by courtesy, professor of psychiatry in the Dell Medical School. Diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2016, at the age of 48, he serves on the Board of Directors at Power for Parkinson’s, a non-profit organization that provides free exercise, dance, and singing classes for people living with Parkinson’s disease in Central Texas, and globally via instructional videos. He also serves as a Community Advocate for ParkinsonsDisease.net, writing columns about living well with Parkinson’s. He is author or editor of 10 books on a range of topics related to bereavement, anxiety, and spirituality. Currently, he is writing a book on counseling people with Parkinson’s disease, which will be published by Oxford University Press. Follow him on Twitter @PDWise